Solution of the week: Prevailing Wage

Nevada has wasted billions overpaying for labor on government projects

- Tuesday, January 8, 2013

Editor's note: Earlier this year, NPRI released Solutions 2013, a comprehensive sourcebook of research and recommendations in 39 policy areas. Now, each week during the run-up to the 2013 Legislative Session, NPRI is highlighting one of these as its Solution of the Week. If you would like NPRI to speak to your organization about this or another policy recommendation, please contact Victor Joecks at vj@npri.org. Solutions 2013 is also available online here.

Since 1937, Nevada law has required that workers constructing state‐funded public works projects receive a special kind of minimum wage, called "prevailing wage."

To the uninitiated, prevailing wage laws sound like they are intended to ensure that workers receive wages reflective of the local labor market. The Nevada Labor Commissioner, however, administers these laws in a way that ensures trade unions are able to control state-mandated prevailing wage rates.

This bias in favor of trade unions leads to wage rates far above those found on the local labor market. This inflates the labor cost component of public works projects — straining taxpayer resources and ultimately limiting the number of projects that can be completed.

Key Points

Survey methodology is flawed. State‐mandated prevailing wage rates are determined through a survey administered by the Labor Commissioner. The way the Labor Commissioner structures the survey, however, leads to a "sampling error" — meaning that the representation of unions among the responses is far higher than among the actual population. For a number of reasons, nonunion contractors incur far higher accounting costs to complete the survey than union contractors.

After the Labor Commissioner's survey has systematically excluded most nonunion contractors, if at least 50 percent of reported billable hours for a given job classification were subject to a collective bargaining agreement, the survey results are dismissed. In that case, Nevada Administrative Code 338 stipulates that the "prevailing wage" must equal the union wage.

State‐mandated prevailing wages are 45 percent higher than market wages, on average. The flawed survey methodology allows unions to unilaterally dictate wage rates paid on public works projects in Nevada. As a result, workers on these projects typically receive a "wage premium."

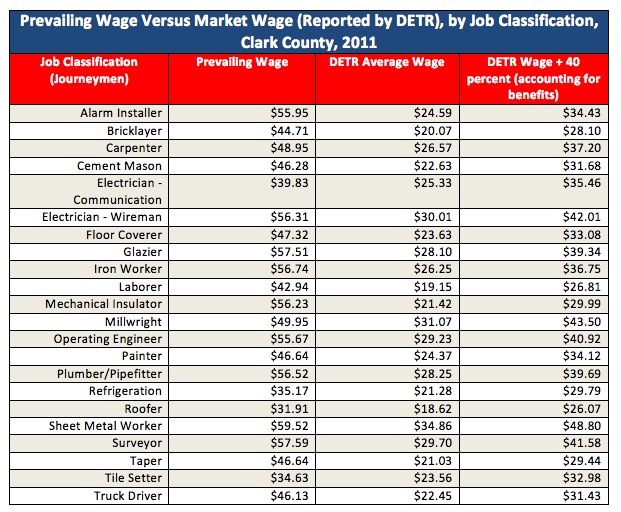

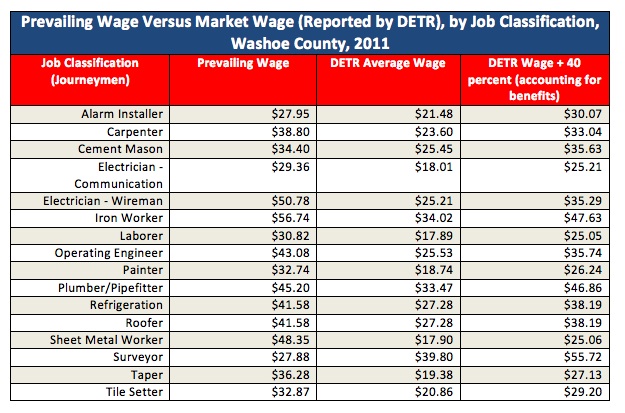

The magnitude of the wage premium can be approximated by comparing prevailing wage rates with wage rates paid in the local marketplace, as reported by the Nevada Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation. These figures show that, on average, workers receive a 44.2 percent wage premium in Northern Nevada and a 45.8 percent wage premium in Southern Nevada.

Wage premiums cost taxpayers a combined $1 billion in 2009 and 2010. When the wage‐premium ratios are applied to the total cost of public works projects undertaken in 2009 and 2010, wage premiums cost taxpayers nearly $1 billion in 2009 and 2010 alone.

Prevailing wage laws are racially discriminatory. Prevailing wage laws in the states are modeled after the federal Davis‐Bacon Act of 1931, which effectively required union wages on federally funded projects.

The explicit intent of the Davis‐Bacon Act was to prevent contractors who employed black labor from winning federal contracts. At the time, trade unions systematically excluded blacks from membership. The Davis‐Bacon Act aimed to undermine the competitiveness of black workers and ensure that unionized, white labor received federal contracts.

Today, black workers remain statistically less likely to belong to a trade union and repeal of prevailing wage laws is "associated with...a significant narrowing of the black/nonblack wage differential for construction workers."

Recommendations

Repeal Nevada's prevailing wage laws. In recognition of the racial discrimination, job loss, expense and other economic distortions that result from prevailing wage laws, 10 states have repealed these laws since 1978. Nevada should become the 11th.

Geoffrey Lawrence is deputy policy director at the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more visit http://npri.org.

Read more: