Solution of the week: PERS

A Utah-style hybrid pension system would protect taxpayers, provide flexibility for government employees

- Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Editor’s note: Earlier this year, NPRI released Solutions 2013, a comprehensive sourcebook of research and recommendations in 39 policy areas. Now, each week during the run-up to the 2013 Legislative Session, NPRI is highlighting one of these as its Solution of the Week. If you would like NPRI to speak to your organization about this or another policy recommendation, please contact Victor Joecks at vj@npri.org. Solutions 2013 is also available online here.

When taxpayers’ contingent liability for Nevada’s Public Employees’ Retirement System is accounted for — through market‐based accounting standards — the system’s unfunded liability currently approaches $41 billion.

That amount is nearly seven times the annual payroll of all state and local governments that participate in PERS. Put another way, the PERS unfunded liability is slightly larger than all spending from the state general fund between FY 1986 and FY 2010 — a period of 25 years.

Obviously, an unfunded liability of such size means that Silver State taxpayers face a tremendous challenge in meeting obligations promised to Nevada’s current and past public‐sector workers. Moreover, given such a burden, Silver State taxpayers cannot allow the PERS unfunded liability to continue growing.

Reversing the growth in unfunded pension liabilities will require a significant restructuring of benefits.

Key Points

Defined‐benefits (DB) pension plans leave taxpayers vulnerable. The growing unfunded liability to which Nevada taxpayers are exposed stems from the fact that the pension benefits promised to retirees are certain, while PERS’s investment returns are not. When a year’s investment returns fall short, PERS increases taxpayers’ required annual contributions to make up the difference. Thus, taxpayers — in addition to bearing the risk on their own retirement savings — are forced to bear the PERS system’s investment risks as well.

Defined‐contribution (DC) retirement plans offer taxpayers greater assurance. DC plans inoculate taxpayers from PERS investment risk. Similar to a private-sector 401(k), in a DC plan taxpayers would contribute a set amount into government workers’ personal retirement accounts, and then, government workers would assume their own investment risk — as do most private‐sector workers.

DC plans benefit government workers. If Nevada shifted to a DC retirement system, government workers would see many important benefits. First, DC plans are both personal and portable. Under the current, collectivized DB system, workers cannot take their retirement savings with them if they change jobs, resulting in “job lock.” Portability of retirement benefits can make public service more attractive to younger workers.

Second, retirement savings in a DC account are a tangible asset that retirees can pass on to their children in case of death. This is not true of a DB plan. In the case of early or untimely death, retirees in a DB program lose their claim to full pension benefits even though they may name a “survivor” to receive partial benefits. In this case, retirees can become net losers, having contributed more money into the collectivized system than they and their survivors will ever receive.

Shifting to a DC plan can be costly in the short term. As PERS administrators have noted, an abrupt, ill‐planned shift to a DC plan could accelerate the amortization schedule of the unfunded liabilities that Nevada’s DB plan has already incurred. Such a shift would require larger taxpayer contributions until PERS collects enough assets to cover its accrued liabilities. Although already destined to incur these costs, taxpayers would have to do so on a shorter timeline.

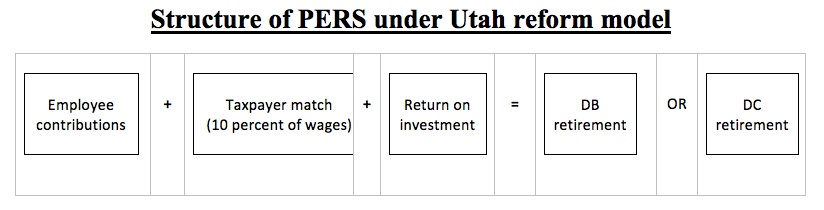

A hybrid approach allows such short‐term costs to be avoided. Utah created one such hybrid plan in 2010. It allows workers to participate in either a DB or DC retirement plan but it limits taxpayer contributions in either case to 10 percent of the workers’ pay. Because Utah will continue its DB plan on an optional basis, its taxpayers will be able to avoid an accelerated amortization schedule for the DB system’s accrued unfunded liability.

Recommendations

Restructure pension benefits around a Utah‐style hybrid system. Nevada lawmakers should protect Silver State taxpayers from the open‐ended liabilities associated with DB pension plans by adopting pension reform along the lines of Utah’s hybrid system. Utah’s system was put in place with the enactment of Senate Bill 63 from Utah’s 2010 General Legislative Session, which should serve as a model to guide Nevadans.

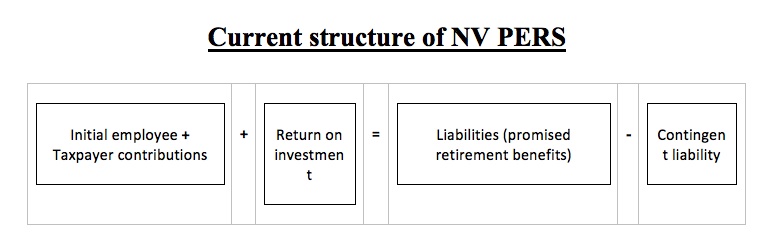

1. Initial contributions. State employees contribute a percentage of their salary toward retirement and that amount is matched by state taxpayers. These contributions currently total to 23.75 percent of wages for regular employees and 39.75 percent of wages for police and firefighters.

At the local government level, retirement contribution rates are subject to collective bargaining agreements and, in many cases, retirement benefits are completely funded by taxpayers with public employees making no contribution toward their own retirement.

2. Return on investment. PERS administrators invest the retirement fund contributions made by employees and taxpayers in a combination of stocks, bonds and private equities in order to gain capital earnings. Currently, PERS’ targeted rate of return is 8 percent per annum, although PERS average annual yield over the past 10 years has been only 3.8 percent.

3. Liabilities. PERS is responsible for paying retirement benefits to participating employees calculated as a percentage of their highest-earning 36 consecutive months of employment. Calculating the total future liability facing PERS can be difficult because so many variables are involved, including: length of career, life expectancy, future pay raises, etc.

4. Contingent liability. Any time PERS’ investment earnings fall short of its annual 8 percent target, its assets fail to keep up with its accrued liabilities (the retirement promises made to government workers). As a result, a corresponding share of PERS liabilities becomes “unfunded.” To account for this unfunded liability, PERS increases the mandatory taxpayer contribution rates in subsequent years. Over time, retirement contributions grow to consume an ever larger proportion of state and local government finances — especially within local governments whose collective bargaining agreements exempt workers from contributing to their own retirement.

Geoffrey Lawrence is deputy policy director at the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more visit http://npri.org.

Read more: