Ineffectiveness of class-size reduction underscores problems with public education in Nevada

Objective data show Nevada doesn't spend its education dollars wisely

- Wednesday, August 7, 2013

Nevada’s public education system is failing and has been for years.

That recognition is nearly universal among Silver State policymakers and informed citizens. Few observers, however, have pointed out that while Nevadans spend much more to support their public education system than do residents of neighboring states, much of that spending goes into programs that do not yield significant improvements in student achievement.

Class-size reduction — one of Nevada’s costliest education expenditures — is one such example.

Since FY 1991, Nevadans have spent $2.21 billion to support a program of class-size reduction for grades K-3. During the 2013-15 budget cycle, this program will cost Nevadans an additional $330 million. The program is intended to keep class sizes in grades K-2 below 18 and the sizes in grade 3 below 21 so that teachers can spend more individual time with each student.

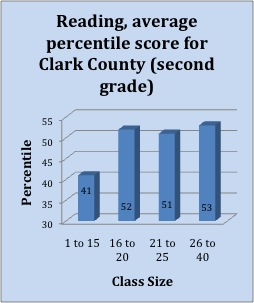

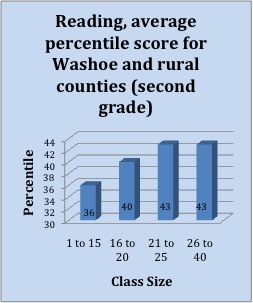

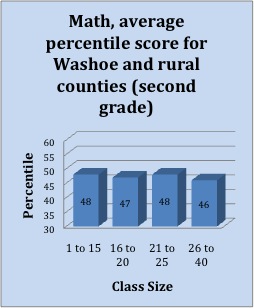

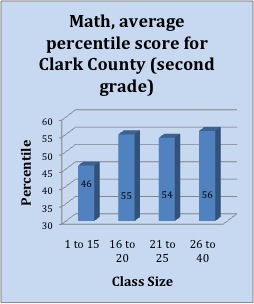

The program enjoys obvious popularity among union officials, since reduced class sizes mean more dues-paying teachers must be hired into public school districts. However, data now show that the program’s impact on student achievement is extremely cost-ineffective. Reviews of the program’s effectiveness by Nevada’s non-partisan legislative staff have even shown that students in Nevada’s larger classes have outperformed students in smaller classes.

|

|

|

|

The relative ineffectiveness of class-size reduction, when it comes to improving student achievement, is not a fact unique to Nevada, either. Stanford education scholar Eric Hanushek and others have used nationwide data to show that even a costly 10-student reduction in class size does not have as great an impact on student achievement as improving the quality of the teacher by one standard deviation. Thus, policymakers could bring about a much more cost-effective improvement in student achievement by improving teacher training or by creating incentives for more talented individuals to enter the classroom.

Alternative paths for obtaining teacher credentials can open up teaching as a viable second career for talented individuals who have already spent years practicing valuable workplace skills. At the same time, creating the possibility of very high compensation for the upper echelon of teaching talent can be an important motivating factor for ambitious young college students — leading them to choose teaching as a career in lieu of other occupations such as finance or engineering.

As Hanushek and other researchers have shown, it’s possible to accumulate data on various education programs nationwide and calculate each program’s likelihood of improving student achievement. Thus, policymakers can construct a rational “purchase list” of education spending instead of blindly throwing money into the programs sought by interest groups who hope to benefit from the increased spending.

Unfortunately, Silver State policymakers chronically resist taking advantage of this objective research and the genuine benefits for Nevada’s school children its implementation would mean.

Instead, special-interest groups, including the state teacher union, have been allowed to control the legislative debate and channel education dollars into the ineffective programs they prefer, notwithstanding those programs’ demonstrated inability to accelerate student achievement.

Keeping this status quo in place is the reflexive belief — encouraged by those same interests — that simply increasing spending will improve the quality of Nevada’s public education system. Yet, as official data from the U.S. Department of Education show, Nevada has nearly tripled per-pupil spending on an inflation-adjusted basis in the past 50 years and now spends more than a majority of its neighbors.

In FY 2010, Nevadans spent roughly $600 more per pupil on public schools than Arizonans, $1,650 more than Idahoans and $1,950 more than Utahans. Yet, these higher spending amounts have not translated into better student achievement. In fact, children in each neighboring state that spends less than Nevada outperform Nevada’s children on standardized tests and in graduation rates.

In FY 2009, Nevada outspent 12 states on a per-pupil basis. Yet, 10 of those 12 states still outperformed Nevada on both the eighth-grade NAEP math and reading tests, and an 11th outperformed Nevada on the reading test alone.

This poor correlation between spending levels and student achievement reveals, once again, that how the money is spent is more important than how much is spent.

Comparing what Nevadans already spend to support their public education system to those in surrounding states, or to the rest of the developed world, shows that Silver State public schools have more than enough resources to produce quality graduates. But to do so, the current spending structure needs to be demolished and reconstructed along rational lines — taking advantage of the knowledge education researchers have accumulated over many years of work.

So long as Nevada’s education spending and the public discourse surrounding it are directed by special interests, rather than the findings of genuine research, this state will continue to leave each new generation handicapped — and unprepared for the challenges of a changing world.

Geoffrey Lawrence is deputy policy director at the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more visit http://npri.org.