Follow Florida on education reform

Don’t be fooled by attempts to distort Florida’s record

- Monday, February 28, 2011

Senate Majority Leader Steven Horsford said recently that, "You can't maintain an ideological position that keeps you from tackling the real problems of the state in ways that are courageous."

While Horsford was referring to Gov. Brian Sandoval's opposition to tax increases, he may as well have been referring to his own and his fellow Democrats' opposition to substantive and proven education reforms.

Educational achievement, or rather the lack thereof, is a real and well-documented problem in Nevada. Education Week reports that Nevada's graduation rate is a nation-worst 41.8 percent, and many of the students who do graduate aren't ready for college. Of students using the Millennium Scholarship, 27 percent have to take remedial college courses.

What's sad about this is that proven education reforms have been implemented around the country and have taught us the kinds of policies that work.

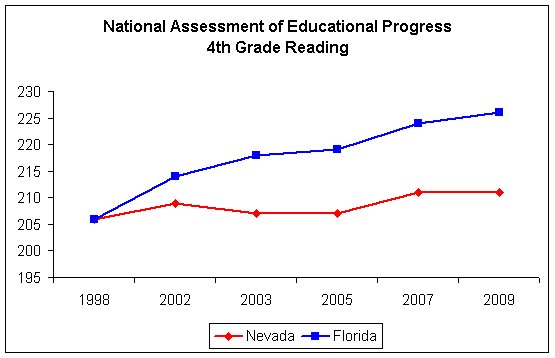

The best state with which to compare Nevada is Florida. In 1998, Florida and Nevada posted the same score on the National Assessment of Educational Progress fourth-grade reading exam. Starting in 1999, then-Florida governor Jeb Bush instituted a series of education reforms, including:

- a corporate-tuition scholarship program that allows more than 23,000 low-income students to attend the school of their parents' choice;

- the largest virtual-school program in the nation, with more than 80,000 students learning online;

- a robust program of charter schools (autonomous, privately run public schools), through which 350 charter schools serve more than 100,000 students;

- the McKay Scholarship program, which sends more than 20,000 special-needs kids to the public or private school of their parents' choice;

- strengthened curricula and assessments, including a very clear and public system for grading schools on an A-through-F basis;

- a ban on social promotion out of the third grade (passed in 2002) — if a child cannot yet read, he or she repeats the grade or takes a remedial summer-school program;

- a new approach to teacher recruitment, including genuinely alternative pathways allowing adult professionals to become state-certified; and

- scholarships for students to leave failing schools (declared unconstitutional by the Florida Supreme Court in 2006).

Twelve years later, the results speak for themselves.

(Ten points is equivalent to approximately a year's worth of learning.)

Florida's gains have been especially dramatic among its Hispanic, African-American and low-income students, as each group has progressed 2 ½ grade levels in learning. Florida's white students have improved 1 ½ grade levels.

Some Democrats have tried to claim that Nevada can't replicate Florida's reforms and subsequent success, because Florida spends more money per pupil than Nevada does. While the claim of a funding increase is true, it was minimal. So money didn't cause Florida's gains.

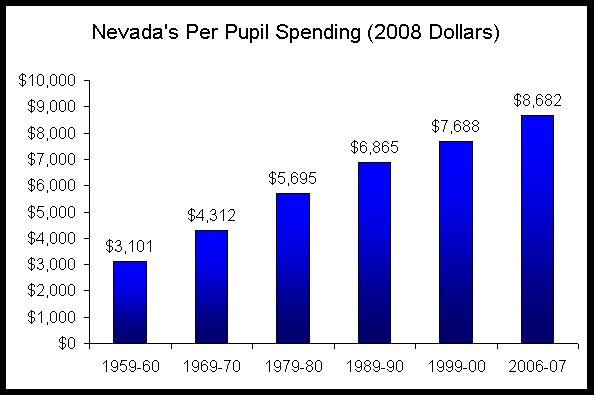

In 1997-98, when Florida and Nevada posted the same score on the NAEP fourth-grade reading exam, Florida spent $8,093 per pupil (this and all following numbers are adjusted for inflation), while Nevada spent $7,536 per pupil. Since then, Florida's per-pupil spending increased by $1,298 (to $9,391 in 2006-07, the latest year for which data is available), while Nevada's spending increased by $1,146 (to $8,682, in the same time frame). Thus Florida increased per-pupil spending by only $152 more than did Nevada. For context, that $152 was less than 2 percent of Nevada's total per-pupil spending.

Others have attributed Florida's success to its pre-K and class-size reduction programs. The problem with this analysis is that Florida's pre-K program wasn't implemented until 2005, and the earliest it could have impacted test scores on the fourth-grade reading test was 2010. Currently, NAEP scores are only available through 2009. While the class-size reduction amendment was approved in 2002, implementation has been slow, and a recent Harvard University study found that Florida's class-size mandate has had no impact on student achievement.

While acknowledging Nevada's dismal educational performance, most Nevada Democrats have maintained their allegiance to the teacher unions' ideology, which claims that "[r]eform done right costs a lot of money."

While this assertion ignores the fact that most of Florida's reforms either save money or are revenue-neutral, and that Florida and Nevada had similar spending increases over the past 12 years, what's more important to note is that Nevada has been trying to solve its education problems through funding increases for decades. In the past 50 years, Nevada has nearly tripled its inflation-adjusted, per-pupil spending, and educational performance has remained stagnant.

(Source: National Center for Education Statistics at the U.S. Department of Education)

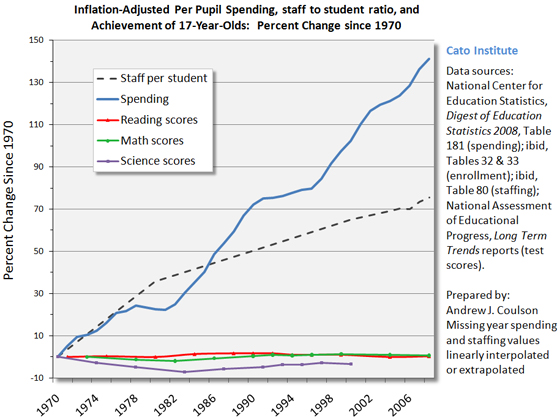

Nevada isn't the only state that has tried to spend its way to academic success. This has been a national trend for 40 years, producing no positive correlation between student achievement and increases in spending and/or the number of school employees.

(Source: CATO Institute)

Instead of proposing fundamental reforms or demanding accountability for the billions of dollars Nevada already spends on education, legislative leaders have proposed a series of quite minor education reforms, including:

- three-year, rather than one-year, probationary status for new teachers;

- a performance-pay system;

- changes to the teacher-evaluation process and tenure system; and

- the formation of a separate state board to govern charter schools.

None of these bills has yet been introduced, so final judgment will have to wait until the actual language is produced.

Still, these ideas are roughly equivalent to giving a starving man a peanut. Is it the right thing to do? Yes, but to assume it will fix the problem is crazy.

The evidence shows clearly which educational reforms work. What's not so clear is whether legislative Democrats, in the words of one of their leaders, will give up "an ideological position that keeps you from tackling the real problems of the state in ways that are courageous."

Victor Joecks is the communications director of the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more visit http://npri.org/.

Read more: