All eyes on Arizona

Will the voters of the state declare sovereignty over its federally administered lands?

- Monday, November 5, 2012

As Americans head to the polls for Election Day 2012 tomorrow, major media outlets are fixated on the changes that will occur in Washington, D.C. But state leaders across the West should focus their eyes elsewhere — specifically, on the results of an important ballot question now before Arizona voters.

That's because Arizona's Proposition 120 has important implications for the federalist system of government with ramifications that are particularly powerful for Western states like Nevada.

Its passage could well be the populist rallying cry that solidifies Westerners' resolve against the land dominion of federal agencies.

Proposition 120 has three components. First, it would declare that each state possesses full attributes of sovereignty on an equal footing with all other states. This "Equal Footing Doctrine" is rooted in U.S. constitutional law and is frequently referenced by Westerners who believe that congressional requirements for Western states to forever give the federal government right and title to much of the land within their borders are unconstitutional. Eastern states were never subject to these punitive conditions, say Westerners.

Second, Proposition 120 would amend Arizona's constitution to remove the disclaimer of interest in public lands that Congress, through the state's Enabling Act, extorted from the state's founders.

Second, Proposition 120 would amend Arizona's constitution to remove the disclaimer of interest in public lands that Congress, through the state's Enabling Act, extorted from the state's founders.

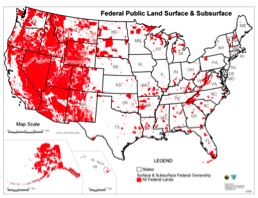

Nevadans have already taken these first two steps, and were among the first to do so. Perhaps that's because no state suffers more under federal-land dominion than does the Silver State, where federal authorities command about 85 percent of the land surface. In 1979, Nevada lawmakers enacted the original "Sagebrush Rebellion" statute, declaring that the state's Equal Footing rights had been violated and that, because federal lands are not taxable, this condition severely hampered the state's ability to finance public services.

Next, in the late 1990s, Nevadans amended their state constitution to remove the disclaimer of interest in public lands that Congress had initially imposed on the state's founders. The measure secured unanimous support in both chambers of the Nevada Legislature in consecutive sessions and then received overwhelming popular support as a 1996 ballot question. A curious footnote to Nevada's current constitution, however, indicates that the amendment still requires congressional action to become effective. And Congress, for the past 16 years, has refused to take such action.

Arizona's Proposition 120 goes a step further, however. It amends that state's constitution to declare Arizona's "sovereign and exclusive authority and jurisdiction over the air, water, public lands, minerals, wildlife and other natural resources within the state's boundaries."

The ballot question draws from a Utah bill passed earlier this year that sets a hard deadline — Dec. 31, 2014 — for federal authorities to transfer title of public lands back to that state. Avoiding the congressional-action dead-end that stymied Nevada's efforts, these new laws would lay legal claims in direct conflict with federal law. This conflict would give both states legal standing to challenge federal authorities before the U.S. Supreme Court, where one of the most significant federal issues in American history could finally be resolved.

A version of the Utah law (HB 148) was introduced earlier this year in the Arizona legislature (as SB 1332), where it received overwhelming support from both houses. It was later vetoed, however, by Gov. Jan Brewer, whose veto message indicated that she didn't truly understand the bill's purpose.

Brewer and other apologists for federal-land dominion have made a number of arguments for their position, all of which are red herrings. First, they claim that the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution prevents states from passing laws which conflict with any federal law, including provisions within the state Enabling Acts. This short-sighted view overlooks the possibility of Congress passing unconstitutional laws itself. Thereupon, it is perfectly reasonable for states to pass contradicting laws in order to attain legal standing and to challenge potentially unconstitutional federal statutes before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Second, Brewer claimed — in direct contradiction to legislative staff reports — that shifting control of public lands from federal to state authorities would have a sizeable fiscal impact. She believed it would cost Arizona taxpayers an additional $23 million annually to manage those lands. She appears to have willfully ignored the possibility of transferring lands controlled by the government back to the people through private auction. Indeed, SB 1332 explicitly spelled out privatization of unused government lands as one of the law's primary objectives. By selling off these lands and entering them into the private property tax rolls, lawmakers hoped to realize an immediate cash infusion as well as a new, ongoing revenue source that would help to fund public education.

There are some key differences between the approach of Proposition 120 and that of Utah's HB 148. Proposition 120 would go further than HB 148 by laying claim to lands under control of the National Parks System in addition to those occupied by the Bureau of Land Management. This difference has elicited widespread attention, because it would allow Arizona to control the commercial activities and public revenues connected with the Grand Canyon.

While some observers may not have the appetite for this more aggressive approach, there's little reason to think that states couldn't operate trust lands, including parks or monuments, at least as well as, if not better than, federal authorities. After all, the feds' poor record of land stewardship has been a hot issue for those who advocate Proposition 120 and other measures to transfer federally commanded land to the states. Insufficient permitting for both logging and grazing on lands controlled by the federal government, for example, has led to vegetative overgrowth on these lands and devastating wildfires across the West.

In Arizona, land-transfer advocates have noted that federal mismanagement of trust lands is partially to blame for wildfires destroying the natural habitats of the spotted owl and the goshawk. Nevada lawmakers expressed similar concerns about federal mismanagement of trust lands when they passed the original Sagebrush Rebellion statute in 1979.

Proposition 120 is giving Arizona voters a chance to join with Utahans and Nevadans in the fight for equal-footing rights. If approved, it will send signals across the West and the entire country that the time has arrived to challenge federal authority and force a resolution before the U.S. Supreme Court.

For Carson City, that will mean a chance to re-up the ante with new land-transfer legislation for Nevada when lawmakers arrive in early 2013.

For that reason, as the rest of the nation fixates on possible change in Washington, Nevadans should also have their eyes focused squarely on the news coming out of Phoenix.

Geoffrey Lawrence is deputy policy director at the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more visit http://npri.org.